Developments make research into Cambodian politics even more urgent

We can learn about our own context by studying governance in other countries. How do we uphold democratic rights in Sweden?

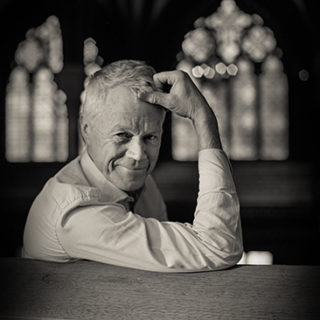

Astrid Norén Nilsson, at the Centre for East and Southeast Asian Studies, is researching politics in Cambodia. Since 1979, the country has been dominated by the Cambodian People’s Party and its prime minister Hun Sen – whose 32 years in power make him one of the longest-serving political leaders in the world.

Like many other countries in Southeast Asia, Cambodia is formally a democracy but characterised by a regime with authoritarian traits. For the first time, the democratic opposition came close to victory over the ruling party in the 2013 national elections.

‟I was interested in investigating perceptions of democracy and citizenship in a country where many political ideologies have left a profound impression, but the same party has been in power for four decades. What drives democratic change forward – and what will politics in Cambodia become?” says Astrid Norén Nilsson.

During 2013–2014 she conducted a study of 192 Cambodians including civil servants, political activists, factory workers and farmers, to investigate their perceptions of donations from political parties, a practice which has marked the country’s democratic era. Her interviews showed the existence of strong popular resistance to these donations – even among Cambodians who supported the governing party.

‟Political donations have lost legitimacy among the masses. There seems to be a desire for change – also confirmed by the latest election results.”

Since she conducted her study, however, the political climate in Cambodia has hardened. Demonstrators are prosecuted for fictitious offences, demonstrations are broken up by the military and opposition politicians are persecuted. The Cambodian government has also introduced new laws enabling the dissolution of political parties – a move which could result in the main opposition party being dissolved before the national elections in 2018.

” We know relatively little about ordinary Cambodians’ political preferences. “

These developments make research into Cambodian politics even more urgent, according to Astrid Norén Nilsson. Especially since the political climate has hardened in large parts of Southeast Asia, even in countries which have long been considered economically and politically stable, such as Thailand and the Philippines. Thailand is now governed by a military junta, while the incumbent president of the Philippines has sanctioned the killing of thousands of people in an offensive against the drug trade.

It is difficult to say what underlies this tougher climate for democratic and human rights, in Norén Nilsson’s view. One explanation could be persistent power structures, built up around authoritarian leaders and clientelistic politics, despite the fact that the countries in Southeast Asia are members of the UN and have committed to upholding the universal declaration on human rights, and despite increased international connections and growing tourism drawing the world’s attention to the domestic politics of these countries.

Astrid Norén Nilsson believes the political currents in Europe and USA could negatively affect developments. Previously, democracies such as the US and countries in Europe could be seen as polar opposites to authoritarian regimes – they could also be an inspiration for the inhabitants of these countries, even if Western democracy needs to be defined and adapted to an Asian context. Now, with right wing extremist parties advancing in Europe and Trump as president of the USA, this opposition has disappeared, according to Norén Nilsson. This leaves the authoritarian leaders in Southeast Asia free once again to control how political power is exercised.

‟We know relatively little about ordinary Cambodians’ political preferences – this is true both of academics and of the Cambodians in power. Through my research, I can contribute to identifying the political ambitions of various groups – and build up a theory about perceptions of democracy and citizenship in non-liberal states. Without such knowledge, we can hardly understand, and much less work for, democratic development in the country.”

Last but not least, Astrid Norén Nilsson thinks that we in Sweden also have something to learn from the political systems in Cambodia and other countries in Southeast Asia. In her view, we often don’t think about what is happening in that part of the world – but it is at least as important to monitor the political currents there as those in the US and Europe.

‟By becoming more aware of what happens in Southeast Asia, we get a better understanding of how the world upholds democratic rights. We can also get a reminder of our own situation in Sweden, by discussing and comparing different models of governance.”

At the moment, Norén Nilsson is researching various individuals and social movements that are mobilising ordinary Cambodians, both to see what versions of democracy are presented through them, and to see how and where politics ‟happen” in Cambodia today.

Text: Noomi Egan

Facts

-

Clientelism

-

denotes a relationship between people with different economic and social status that involves a mutual exchange of goods and services. The relationship is based on a personal connection and is generally perceived as a moral obligation.