Drone images could solve African farming mystery

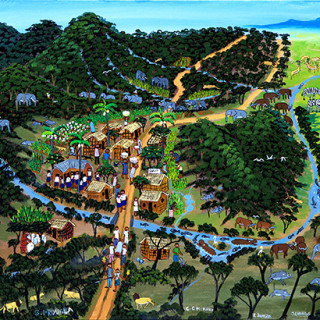

The key to increased well-being in Africa lies in improving small scale farming – at least if you want to see improvements within a foreseeable future, according to Göran Djurfeldt. Together with Ola Hall, he has now launched a project using drones to understand why harvests vary so much from one field to the next, despite apparently similar conditions.

Göran Djurfeldt is one of Sweden’s foremost experts on African agriculture. Together with Agnes Andersson Djurfeldt and Magnus Jirström, he has been running Afrint, a major project on the intensification of African agriculture, for just over a decade. Within the project, African and Swedish researchers have conducted extensive interviews with people from 4000 smallholdings in nine African countries. The aim is to be able to follow development over time, to see which of the smallholder’s methods and maintenance strategies work and which do not. Insufficient use of fertiliser, excessively small plots, bad seeds and long distances to markets have emerged as the most important reasons for smallholders’ difficulties in living off their land. But these factors do not explain everything.

“In Sub-Saharan Africa, 70 per cent of people live off agriculture and as the population is expected to double by 2050 it is important to produce as much as possible on the arable land available”, says Göran Djurfeldt.

In order to fully understand why two farmers with apparently similar conditions can still have such different harvests, interviewing the farmers is not sufficient. This is why the researchers decided to complement the interviews with remote analysis technology, i.e. satellite images from cameras which register humidity, vegetation and heat. This provides the researchers with a physical map showing the quality of the cultivations and the soil.

“We can see whether the plants are stressed, there are too many weeds or the soil is too dry”, says Ola Hall, who joined the Africa researchers because of his specialisation in studying agricultural development through satellite images.

“Drones which fly below the cloud cover can take more detailed images.”

It is difficult to use ordinary satellite images in Sub-Saharan Africa, however, as fields are small and there are a lot of clouds in the way. This is why Ola Hall and Göran Djurfeldt are now testing cameras mounted on drones which fly below the cloud cover and can take more detailed images.

“We have been in Kenya to conduct test-flights and the technology works well”, says Ola Hall, explaining that the drones will initially be used in four of the villages included in the Afrint project: two in Kenya and two in Ghana.

The project also involves sociologists and human geographers from Lund University, as well as agronomists from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU. This means the remote analysis images and interviews will be complemented with physical samples of soils and plants.

“We will cover all factors which can affect the harvests. From soil and agricultural techniques to local governance of the villages and division of land”, says Göran Djurfeldt. “The idea is to provide governments and aid organisations with the best possible and most applicable explanations for bad harvests. Then we can work on developing better methods and more effective advice.”

Not all the villages documented in the Afrint project will be photographed using the researchers’ drones. However, the researchers will compare existing satellite images with drone images to become better at deciphering the less detailed satellite images. As the satellite images cover a longer period of time, they enable researchers to observe changes in agriculture attributable to external factors, such as climate change.

In several countries in the western world, including the US, the use of satellite imagery and remote analysis in so-called precision agriculture is increasingly common. The idea is to become more environmentally friendly and not to irrigate or fertilise more than precisely needed, but also to maximise harvests.

Göran Djurfeldt draws parallels between today’s African smallholders and Sweden in the 1800s:

“The problems of farmers in Småland, for example, could perhaps have been solved if there had been more knowledge about the land, allowing agricultural methods to be adapted to the the soil”.

Text: Ulrika Oredsson

Photo: Gunnar Menander