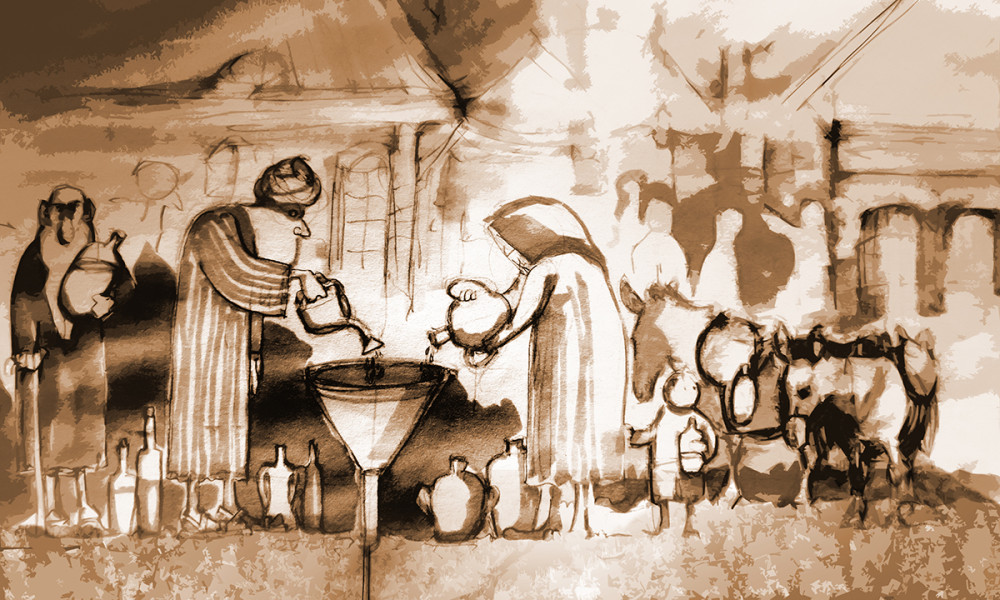

Water mafia take advantage of the poor

Despite rules and legislation on water for all at a reasonable cost, water shortages hit the poor hardest. In slums in large cities, illegal water mafia have emerged that take advantage of people’s desperate need for water. Maryam Nastar has studied water politics in two fast growing cities, Hyderabad in India and Johannesburg in South Africa.

These cities both have visions of access to clean water for all. However, in the slums in India that I have studied, it turned out that people only had access to water a few times a week. In areas without water mains, poor households are dependent on water from tankers. They have to pay more per litre than households that are connected to the mains”, says Maryam Nastar.

Hyderabad is one of India’s largest cities, with a population of almost seven million people. The city is growing rapidly, and is a centre for the IT and pharmaceutical industries. Johannesburg is also a city of over a million people and it is South Africa’s leading commercial and financial centre. Both cities have clearly declared a vision of equality for all. Yet the cities have a history of inequality – with the former apartheid system in South Africa and the caste system in India.

The cities also have large slums – as many as a third of the inhabitants of Hyderabad live in houses without running water, drainage and electricity.

“Water supply in these areas can be organised in various different ways”, says Maryam Nastar. “Sometimes a tap is shared between several families. Sometimes tankers deliver water a few times a week to the district, and in some cases it is suspected that these are owned by an illegal ‘water mafia’ that takes advantage of people’s desperate need for water.”

It was a shocking discovery, explains Maryam Nastar, that with rules and legislation on water for all at a reasonable cost, so many people had problems getting hold of clean water. She also believes that the demands placed on cities by the World Bank as a condition for loans mean that water has to be ‘commercialised’ by the state.

“In practice, this system appears to work no better than the privatisation of water that the World Bank finally decided to stop pursuing ten years ago after much criticism.”

According to Maryam Nastar, water shortages in the growing cities in developing countries are not only a consequence of climate change; they are also the result of unfair division and distribution of water.

“The issue of water shortages in cities is therefore ultimately a question of the decision-making processes that are affected by the market in combination with historical inequality in these countries”, she says, pointing out that there are things that can be done to improve the situation.

“If disadvantaged groups speak up, then this can have an impact. There are examples of how it has led to cities successfully resisting privatisation of their water supply or to fairer distribution of resources.

“It is important to understand the real reasons behind the water shortages”, says Maryam Nastar. “Only then can we find solutions.”

Text: Nina Nordh

Illustration: Catrin Jakobsson