An epigenetic reflection

Opinion by Ulf Kristoffersson, Consultant at the Genetics Clinic, Laboratory Medicine, Region Skåne and Reader in Clinical Genetics

2014

“I have no responsibility for my own health – it’s my genes that determine whether or not I become ill.”

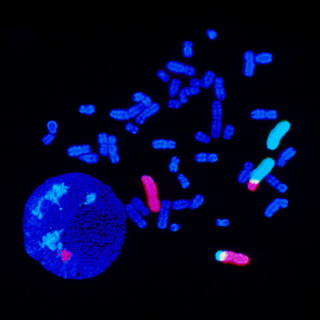

With greater knowledge of the role of our genes in health and disease, some deterministic ideas have taken root among the public. This determinism, which has never been embraced by scientists in the field, does not agree with the new theories. Our lives and lifestyles affect how our genes are expressed and this quashes the reasoning of genetic determinism.

What significance does this have for our relationship to health and health services: do we have greater responsibility for our own health than previously? Maybe, maybe not. We are already encouraged to think about all aspects of our health on a daily basis – not smoking, not drinking, eating a balanced diet and exercising.

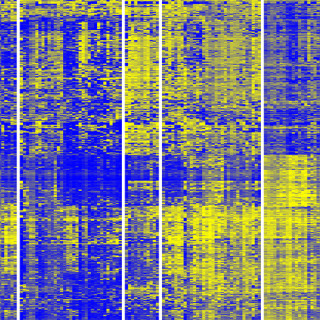

The growing awareness of how epigenetic changes regulate gene expression could lead to the personalisation of this advice, which would be of benefit to the individual. However, the knowledge could also be turned against the individual – if you smoke or eat unhealthily, you run a much higher risk of suffering from disease. Knowledge of your epigenome could also reveal that certain medical treatments will not have any effect, or alternatively, will be particularly effective.

Once such new diagnostic possibilities become available, it will mean that some people will not get treatment. This group have sometimes been referred to as “the new orphans” – those for whom there is no effective treatment. This will entail savings for society because we will not have to pay for ineffective treatments, and overall treatment will become more cost-effective.

On the positive side for the individual, there will be more opportunity to personalise treatment. The individual will receive a better tailored treatment than at present.

From the perspective of society, it is of course possible that we could see discrimination against those who increase their risk of disease by their lifestyle. However, epigenetic tests will never lead to a 100% causal link between an individual’s lifestyle and ill health; there are always other factors involved. Epigenetics will simply provide a new way of classifying individuals into different risk groups. I therefore do not think that greater knowledge of the origins of our different phenotypes will have a direct impact on how we approach others, but of course it could be used to classify people in the same way that we can divide them into fat and thin, smokers and non-smokers, etc. The individual will probably not change his or her behaviour; why should we expect they would? We already know that our bad habits lead to ill health and yet so many of us continue with them. It is more likely that there is a risk of a new hype – overconfidence that I can influence my epigenome to achieve a better life, a life more in line with the prevailing norms.