We eat 25 per cent more meat than recommended

People in Sweden eat 25 per cent more meat than the amounts recommended by the National Food Agency. This is shown in a new study from Lund University that has also investigated the impact on both health and climate change of a corresponding reduction in meat consumption.

The results show that carbon dioxide emissions from the Swedish food sector would be reduced by 10–20 per cent if we reduced our meat consumption to the recommended level. This would also free up agricultural land corresponding to 10–20 per cent of Sweden’s agricultural land.

“Every year, Swedes eat 70kg of meat and meat products, of which 62kg is pure meat. That is 20kg above the recommended level”, says Elinor Hallström, nutritionist and doctoral student in energy and environmental systems at Lund University, who instigated and carried out the research.

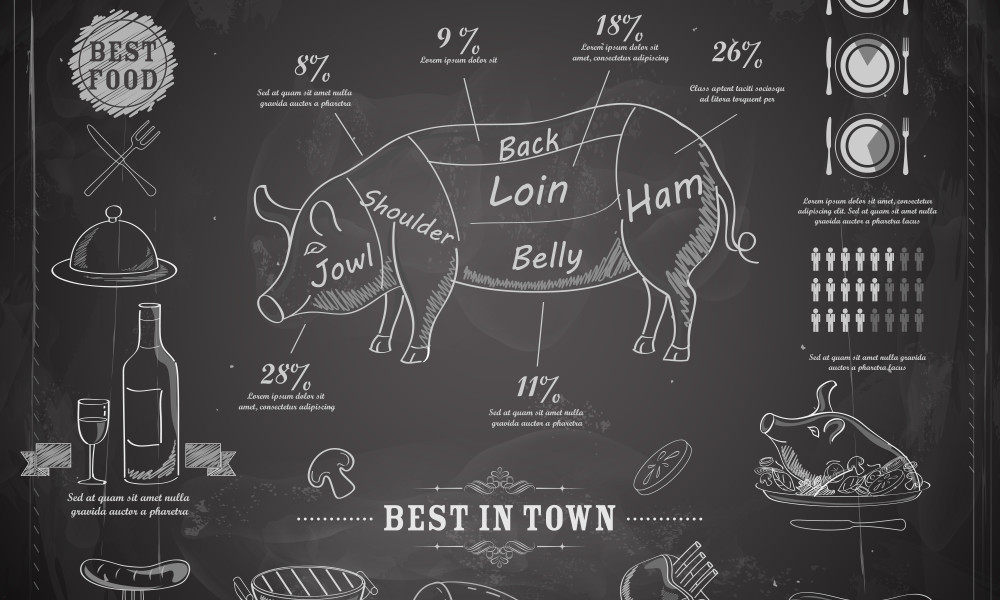

Her findings also show that three quarters of consumption is made up of beef and pork, and one quarter is cured meat products. The figures surprised her.

“Most people know that we should not eat too much red meat. It is also remarkable that cured meats form such a large proportion of meat consumption. Sausages, liver pâté, bacon and other processed meat products contain high levels of harmful fat and increase the risk of certain types of cancer.”

According to Elinor Hallström’s calculations, we would experience nutritional benefits from reducing our meat consumption. Our intake of energy, fat and saturated fat would be reduced, which Elinor Hallström regards as a positive effect, because we generally eat too much of these nutrients. Protein intake would also fall, but this would probably not have a negative effect because most people eat more protein than they need.

On the negative side, intake of iron and zinc would be halved. If the intake of minerals falls too low, Elinor Hallström recommends eating more legumes or other vegetables that are high in zinc and iron, which are particularly important minerals for women of child-bearing age.

Elinor Hallström’s calculations of meat intake are based on unprocessed meat without bones before cooking. This is also what the National Food Agency works from. However, when the Swedish Board of Agriculture talks about meat consumption, this is based on slaughtered weight including bones, which causes discrepancies of up to 30 per cent in official statistics.

“Neither is really right or wrong, but it is confusing for consumers to make comparisons between different measures”, says Elinor Hallström, who recommends that representatives of different bodies make clearer what their figures represent – something that is rarely done at present.

Elinor Hallström’s research was a collaboration with Elin Röös at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, and Pål Börjesson, Professor of Environmental and Energy Systems at Lund University.

Published:2014