The earth we inherit

Opinion by Håkan Wallander, Professor of Soil Biology and Environmental Science, Lund University

2014

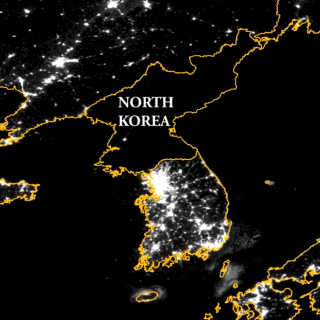

If we divide the earth’s cultivable land between all its inhabitants, each person gets just 2 000 m2. How can we change the way we live so that there is enough space for everyone?

In the 18th century, the major challenge for Swedish farmers was to save nutrients. A lot of meadow was needed to produce fertiliser for a small field that could produce at best a few bushels of corn. Today, we do the same thing on a fraction of the land area.

The productivity of agricultural land has increased exponentially in the past century, primarily as a result of artificial fertiliser, although more efficient farming methods, improved crops and more efficient pesticides have also contributed. However, modern intensive farming methods also lead to problems that we have to deal with. Land that is ploughed is exposed to wind and rain, resulting in erosion. The larger the area, the larger the problem, and it is particularly evident on the Loess Plateau in northern China. Major cultures such as the Han and Tang dynasties were fed by the fertile soil, but today it has eroded away, all due to incorrect farming methods.

“A much larger proportion of nutrients must be returned to cultivated land if we are to be able to feed the earth’s growing population.”

We know the earth’s resources are limited. If we are to continue using artificial fertiliser, phosphorus is required. The minable sources of phosphorus are starting to run out and if we don’t improve the way we recycle phosphorus, we will once again be hit by exhausted land and reduced food production as a result.

In my opinion, we cannot afford to waste this resource. Today, we often remove nutrients from water at sewage works to stop them running into rivers and seas. However, urine, for example, diluted with ten parts water produces an excellent nutrient solution that contains everything plants need. A much larger proportion of nutrients must be returned to cultivated land if we are to be able to feed the earth’s growing population. Otherwise, there is a risk that the exponential growth of the earth’s production capacity may soon be transformed into a steep downward trend.

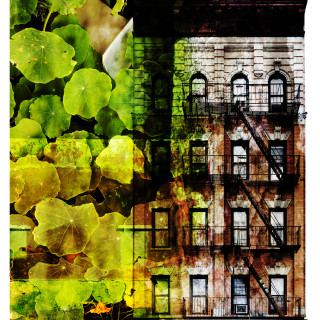

Imagine if we could reduce the devastating effect of ploughing, and instead rely on perennial crops. Progress is currently being made in efforts to develop perennial forms of our most common crops, and if these are successful, both erosion problems and nutrient leaching will be reduced. The ground would not have to be worked as often, which means less diesel consumption and less risk of soil compaction and erosion. The use of artificial fertiliser and pesticides would also fall, which would benefit both farmers and the environment.

Photo: Kennet Rouna