The importance of learning to move correctly before starting strength training

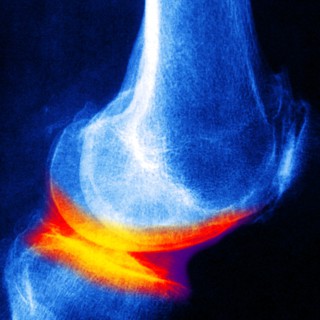

“You must strengthen your leg muscles” is what people with osteoarthritis are often told, and they are encouraged to do strength training and go for long walks. But that sort of exercise is not what they primarily need, according to Eva Ageberg.

“If a person limps when he walks in order to reduce pain in the knee, going for walks won’t help. It just consolidates an incorrect pattern of movement and does not reduce pain over the long term”, she says.

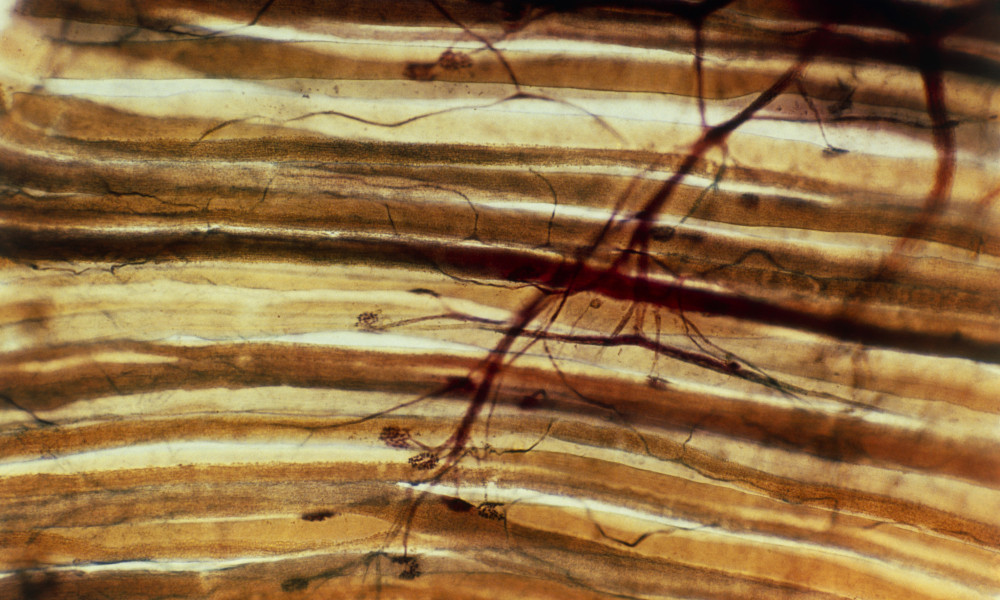

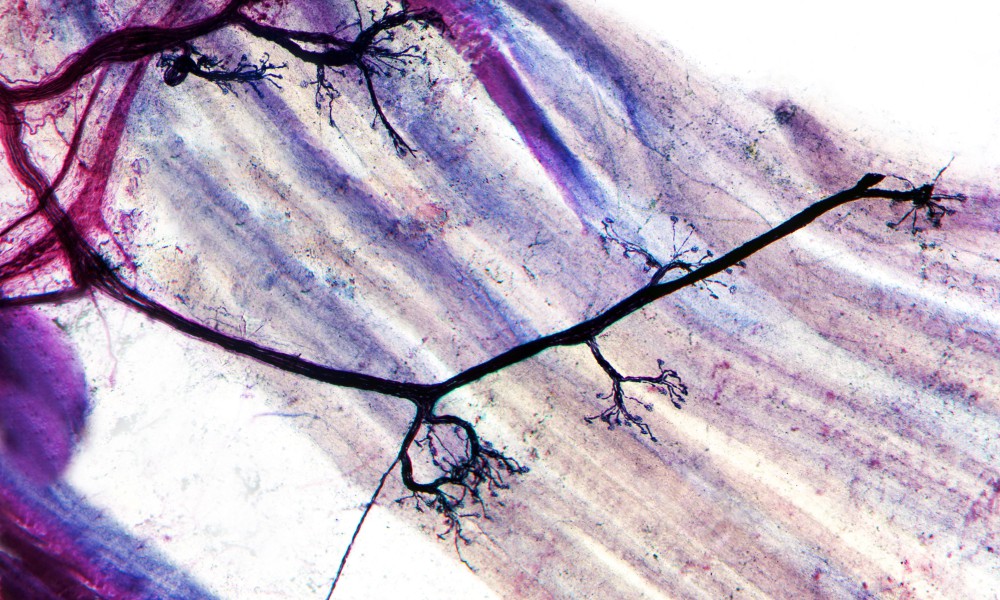

Eva Ageberg, a senior lecturer in physiotherapy, is interested in what is known as neuromuscular training. This aims to get the patient to ‘relearn’ the signals between the brain, the joints and the muscles that have been disturbed by a knee injury or by osteoarthritis. The training starts with everyday functions such as going up and down stairs or getting up from a chair. These are simple movements for those who have healthy bones, but not for those who have pain in their joints.

“If there is pain, the brain’s nerve signals to the body’s muscles before movement do not function in a normal way. The systems that make us aware of ‘where our bodies are’ are not functioning as they should either. So you might not notice, for example, that you have your knee at an unfortunate angle when you move”, explains Eva Ageberg.

Neuromuscular training divides movements into small segments. For example, walking consists of three segments: first you put your heel down, then you stand on one leg, then you push off. The three phases are first practised separately, and then combined into a flow once the patient has got all three of them working.

“At the beginning the patient has to think about each movement. It is exactly like learning a new sport.”

In neuromuscular training, the exercises are adapted to suit the individual and the injury, with training gradually becoming more intensive. These principles are the same for young athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injuries and for elderly people with osteoarthritis of the knee. The symptoms are very similar in these two conditions: the person thinks the joint feels unstable, and the neuromuscular function, posture and body image deteriorate.

Another connection is that one of these conditions often leads to the other. Half of all young people with a knee injury get osteoarthritis approximately a decade later.

“That is why it is so important to exercise in the correct way, even if you are young and do not yet have osteoarthritis”, says Eva Ageberg.

So for Eva, ‘the correct way’ does not mean strength training. By reinforcing isolated muscles, this type of exercise can at worst be directly detrimental to the joints, as strong muscles used in the wrong way can damage the body. Instead, strength training and general exercise should come as a second step, once the patient has learnt to move normally in an optimal way, with no detrimental strain on the body.

Studies conducted by groups both in Lund and elsewhere have shown that neuromuscular training works on young and middle-aged patients with knee injuries. It is also effective for elderly people with osteoarthritis, as shown by a study carried out by Eva Ageberg on patients between the ages of 60 and 77. The patients were waiting for a new knee- or hip-joint due to osteoarthritis, and the training served to improve their physical condition in view of the operation. Although these patients had major problems with their knees or hips, they were still able to carry out the training and improve their function without experiencing more pain than before.

Eva Ageberg’s research team has published its neuromuscular training programme, which is called Nemex, for free use. Other researchers are now using the training programme in order to compare it with the standard treatment. Ageberg therefore hopes that other researchers will join in and compare the programme with other forms of care for knee-injury patients and osteoarthritis sufferers.

Text: Ingela Björck

Published: 2014