Powerful MRI scan gives hope for early diagnosis

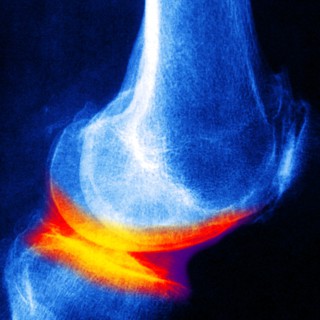

Osteoarthritis can be seen on X-ray images, but only once the condition has progressed so far that the cartilage in the joint has almost entirely worn away. The bone surfaces then rub against one another without a protective ‘shock absorber’, and the joint starts to hurt. Jonas Svensson’s goal is to develop an MRI technique that shows the disease at a much earlier stage.

Jonas Svensson calls himself a fish out of water in the context of osteoarthritis: he is a physicist rather than a doctor. As a medical radiation physicist, he works with image diagnostics of osteoarthritis in close collaboration with Professor of Orthopaedics Leif Dahlberg and other osteoarthritis specialists.

“There is a method to create images of osteoarthritis at an early stage using a contrast agent and MRI scan. The method has been developed here in Malmö and is the best we have at present, but it doesn’t provide sufficiently accurate information. That is why I want to try and develop other methods”, he says.

MRI stands for magnetic resonance imaging. MRI technology is based on strong magnets instead of ionising radiation, and therefore does not endanger the health of patients and research subjects.

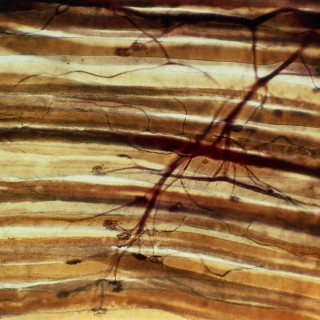

MRI is often used to view the hydrogen in the body, because the water content of different types of tissue shows their different characteristics. Jonas Svensson is going to study two alternative measurement methods, both of which involve measuring the amount of aggrecan, an important protein in cartilage. One of the methods focuses on the hydrogen atoms in the aggrecan molecules, and the other focuses on the sodium ions that are present in healthy, aggrecan-rich cartilage.

In both cases, however, the signals used are much weaker than those with which MRI images are usually obtained.

“An extra strong MRI scanner is therefore needed. Such a scanner is actually on its way to Lund – its magnets will be over twice as strong as those in MRI scanners used in hospitals. The new scanner is a national investment and will only be used for research”, explains Jonas Svensson.

If it becomes possible to monitor the development of osteoarthritis from its start until the condition becomes visible on X-rays, this will provide entirely new insights. Cartilage is difficult to study at the moment; because it doesn’t heal well after injury, researchers are not allowed to take samples of cartilage from living patients. Instead, they have to study either animal models or cartilage from amputated human body parts.

Cartilage is unable to repair itself once the damage is extensive enough to be visible to the naked eye. At an earlier stage, the cartilage has certain natural repair mechanisms. Damage at molecular level – within the molecules of the cartilage – can be repaired through the ongoing renewal of the components of the cartilage. This makes it particularly important to find ways of seeing molecular changes in the cartilage, as Jonas Svensson is now hoping to do using MRI technology.

Text: Ingela Björck

Published: 2013