The huge potential of bioplastics

Nowadays it is possible to produce plastics from sugar or vegetable oils, but up to now fossil oil has been too cheap for the production of bioplastics to be profitable. That explains why the plastic-producing bacteria, developed some years ago by researchers at the Centre for Chemistry and Chemical Engineering (Kemicentrum), are still waiting in the freezer.

Professor Rajni Hatti-Kaul started to research into bioplastics from bacteria at Kemicentrum in connection with a research project that started 15 years ago in cooperation with a university in Bolivia.

“We started with a trip to Bolivia’s salt deserts”, says Rajni Hatti-Kaul. “The bacteria that live there must have special properties in order to survive in such a tough environment with so much salt and so few nutrients. They need to produce their own store of fuel to use when they have no food.”

Back at the lab, the researchers have continued to work on the bacteria they found in Bolivia.

“We have developed processes in which we produce a cell mass that contains up to 85 % bioplastic. We have developed a collection of plastic-producing bacteria, both from nature and using gene technology methods to produce modified types.”

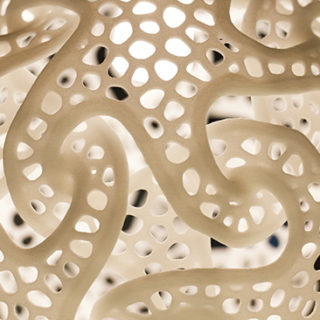

The end result, following the research projects of several doctoral students, is that the bacteria are now in the freezer waiting to be used. The plastic that the bacteria produce from raw materials such as sugar or vegetable oils has properties similar to those of polyethylene and polypropylene plastics sourced from fossil raw materials, but has the advantage of being biodegradable. See adjacent photo – the plastic is the white clumps inside the bacteria.

Oil is still too cheap for bioplastics produced by bacteria to be competitive in price terms. As it stands today, it would be two to four times more expensive to produce than the same product manufactured from fossil raw materials.

“It is often a long path from a lab process to industry. It is frustrating. We have developed several good biotechnical processes for diverse products from renewable raw materials, but in most cases the financing dries up before process and product development are completely ready”, says Rajni Hatti-Kaul.

While waiting for it to become more financially attractive to continue working on the plastic-producing bacteria, the researchers in Rajni Hatti-Kaul’s team are mainly focusing on finding eco-friendlier production methods for bio-based chemicals that act as building blocks for other chemicals and materials. This concerns substances needed for making eco-friendlier plastics, paint additives, textiles, hygiene articles, drugs etc.

“One exciting area, for example, is that we have found an eco-friendlier way to produce polyurethane, which is used in applications such as plastics, foams and glues. Fossil material is still the raw material for this product, but our new techniques do not need isocyanate, which is a toxic chemical. It would also open up new application areas for this plastic, such as medical technology.”

Text: Nina Nordh