“Falsified medicines are a growing and underestimated health threat”

A billion dollar market with fatal consequences. Falsified medicines are a virtually unknown health threat to the Swedish general public, although these drugs are among the ones purchased online. The proportion of Swedes who buy medications online is increasing. “Clear and recurring information on the dangers of falsifications is now a must”, writes Susanne Lundin.

Three bodies in contorted positions. Arms and legs sprawling in different directions; eyes gazing empty. These children are some of the more than 400 Congolese taken ill with so-called acute dystonia that paralyses the muscles. The patients are in a remote area of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and it was almost a coincidence that the WHO only a few weeks ago found out about the accident.

A rapid investigation showed that the common denominator in all those who had fallen ill was that they had taken the drug Salina. According to the packaging, the tablets contained the soothing substance diazepam, but instead they were found to have high levels of the antipsychotic substance haloperidol that leads to severe paralysis, primarily of the face, tongue and neck. The WHO raised a world-wide alert.

I saw the Congo image at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, at a unique meeting of researchers, forensic scientists, medics and pharmaceutical professionals, as well as experts from the WHO and Interpol, that was held in July. The theme was falsified medicines; how they are to be identified and combatted.

The drug Salina is just one of countless examples of falsified drugs that have become a billion dollar market with often fatal consequences for patients. The sales are expected to pull in huge profits, far more than those resulting from drug-related organised crime. A few weeks ago, Interpol conducted the operation Pangea VIII, and in just over one week, they seized various falsified drugs with an estimated value of $81 million. These drugs are in several cases intended to be used to save people’s lives. They can be purchased online and in retail stores in some countries. Or even handed out in good faith by aid organisations in developing countries where people are unaware that the dangerous drugs in many cases are the result of an agreement between a corrupt government and a “company”, and produced in a basement in India or China for example.

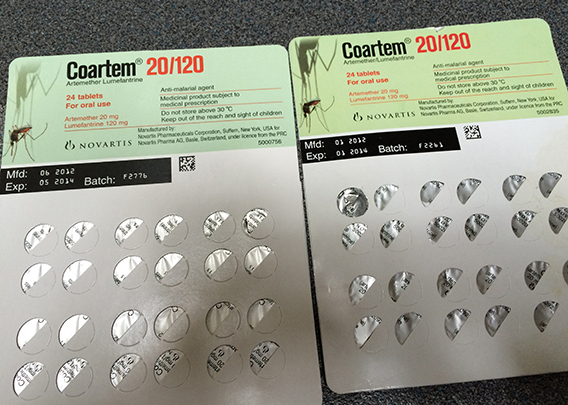

Some of the more common falsifications are those claiming to treat malaria. Every year over 207 million people fall ill to the disease, and can mainly be found in Africa. Lately, there have been some hundred cases per year in Sweden, of which all patients were infected abroad. The WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network recently discovered that 35 per cent of all anti-malarial medication was falsified. In Nigeria, these figures were as high as 64 per cent. Other medications that are often falsified are those said to combat HIV/AIDS, TB and recently Ebola.

Falsified medicine is a severely underestimated problem and virtually unknown to the general public in Sweden. How many know that Swedish customs just a few years ago seized half a million medicinal products that were falsified, and that Sweden has had the reputation of being an international hub for illegal drugs? As recently as last summer, the police shut down over sixty illegal websites, mainly involving lifestyle drugs, primarily Viagra, weight-loss products, and antidepressants. It is difficult to know to what extent these drugs are effective, but an increasing amount of warning signs indicate that people become ill and, in some cases, suffer severe chronic consequences. Purchases of antibiotics have recently increased. The WHO warns that this may lead to the spread of multi-drug resistant bacteria.

Pharmacies need a permit to sell prescription medications. Yet, there are many who sell prescription drugs without permission online. There are countless falsifications of well-known drugs, but also medications that are no longer effective because they expired many years ago and have been revamped and stamped with a new expiration date. The drugs may contain the wrong levels of the active substance, a completely different substance, or no real substance at all. They often include contaminants such as brick dust, ink, wall paint and floor polish.

A brand new report from the Swedish Medical Products Agency provides a picture of how Swedes relate to online medicines. It turns out that eight years ago, about 3 per cent had purchased non-prescription or prescription drugs online, and 35 per cent would consider it. Three years later, the percentage of those who had bought medication online had increased to 20 per cent. The latest figures are from last year. The questions in the report were mainly about prescription drugs, making it difficult to compare the responses with previous ones. Nevertheless, the interest is clearly growing; 50 per cent of older people think that the internet is a convenient alternative to their regular healthcare provider. That it takes place through an illegal website does not seem to matter that much.

It is surprising that the healthcare system and several decision-making bodies are only superficially aware of the existence of falsified medicines. And it is remarkable that there is so little knowledge about the global market where people are exposed to illegal and dangerous drugs.

I have previously done research on the black market for human organ trade and I see parallels. In my discussions with the UN, the Council of Europe and Europol it became clear that there was a lack of data about organ trade. “We have no information”, said Europol, “and without facts there is neither money nor ability to investigate”. Therefore, initiatives, such as that taken by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, are both gratifying and necessary. Other important initiatives include Interpol’s annual global controls and information from the WHO.

So how can falsified medicines be combatted? Pharmaceutical crimes require broad international cooperation between researchers, police officers and legislators, enabling a common understanding of what falsified drugs are and how these pharmaceutical crimes are to be handled legally. Last spring, the Swedish Government submitted a bill to the Swedish Parliament proposing an amendment to the legislation. This is a very important measure. At the same time, it is questionable whether the proposed penalty of six months to two years in prison is proportionate to the large groups of patients with life-threatening illnesses who believe they are being treated but instead suffer permanent damage or even die.

Clear and recurring information to the public on the dangers associated with purchases online or on the black market is also a must. Such information goes hand-in-hand with the training of healthcare staff, who today may be completely lost when encountering patients with unclear symptoms.

Of course, this also requires an understanding of what can be called health behaviour and knowledge of cultural differences. Norms and cultural values are the basis for how people act. This applies to both cynical dealers of falsified drugs and to the people who use them. Therefore, it is necessary to map the socio-cultural mechanisms. Above all, it is important to highlight the phenomenon of falsified medicines.

Susanne Lundin, Professor in Ethnology at Lund University in Sweden

The article was first published on DN Debatt 3 August 2015