Africa’s renaissance

Opinion by Ellen Hillbom and Erik Green, Readers in Economic History with a special interest in African Economic History

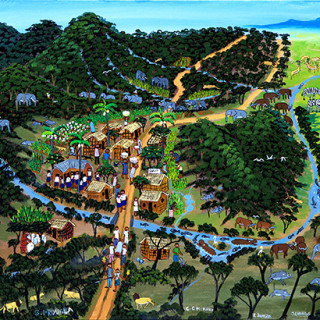

Among the general public and the researchers, Africa has been described as a continent in permanent poverty with weak economic growth. Today the situation is different. Several African countries are among the international growth-leading economies, foreign direct investments are increasing significantly, and we read about new business opportunities in the finance pages in the papers. Africa could be the future in a world where the European and American economies are weakened and China’s extreme growth has slowed down. The regional differences are and have always been major, but the question is whether the time has finally come for Africa’s renaissance?

Economic historians have long opposed the perception of Africa as a historically speaking economically stagnant continent. Instead, they point to several regions that have demonstrated a relatively high growth over extended periods. West Africa 1850–1914, for instance, showed a long period of growth based on the export of raw materials. The problem has been that the growth has never become sustainable, but only been peaks in a wave pattern of large economic fluctuations. From this perspective, the current growth is less surprising. The relevant question is whether it will become the basis for sustainable economic development, which cannot be answered by fixating on growth rates; rather, we must look to the underlying causes of growth and how these differ from previous periods.

Just as before, today’s growth is based on increased exports of raw materials driven by a rise in world market prices. Can we expect Africa to once again end up in a financial crisis when prices go down? There are some indications of this. Investments made in businesses and manufacturing industries are still disturbingly small, and work productivity has remained relatively low. China’s current investments in infrastructure and agriculture are reminiscent of what initially took place during early European colonialism. These investments do not automatically contribute to economic development; rather, they can lock the continent into a dependency on the export of raw materials.

Meanwhile, there are signs indicating that this time things are different. First of all, there are fewer political obstacles to investing in capital inflows in the more productive sectors, thereby diversifying the African economies. European colonialism effectively put an end to such processes as they were not in their best interest. Second, Africa is undergoing a slow transformation from a sparsely populated continent to one with a relatively high population growth. It reduces the cost of investments in the manufacturing and processing industries as the workforce increases, resulting in reduced relative wage costs. Third, new technologies such as the internet and mobile communications have led to a dramatic reduction in the need for fixed investments. Finally, another new feature is the growing African middle class which is an endogenous engine of growth in some economies. Eventually the emerging south-south relations between Africa, Asia and Latin America could open up for new economic collaborations.

Africa continues to grapple with enormous challenges such as widespread poverty, the need for education and healthcare, underdeveloped infrastructure, low-producing agriculture, uncontrolled urbanisation and corruption. But we can perhaps be cautiously optimistic and believe that at least in parts of the continent, Africa’s current renaissance has the long-term potential to evolve into sustainable economic development.