Not to fail those in life’s final stages

End-of-life care – palliative care – means improving the quality of life for patients and their next of kin by preventing and relieving suffering in the final stages of life.

Around 90 000 people die in Sweden every year. According to the National Council for Palliative Care, Sweden has a national average of 42 palliative care beds per 1000 deaths (2010).

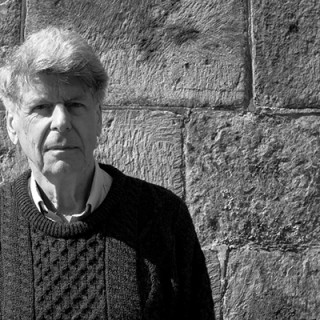

“This means that many people in need do not get access to specialist end-of-life care. We are not making the most of the knowledge we have to relieve suffering and make the final phases of life as calm and dignified as possible”, says Birgit Rasmussen, Professor of Nursing specialising in palliative care at Lund University and Region Skåne.

Palliative development centre in Lund

Birgit Rasmussen works at the recently started Palliative Development Centre in Lund, which is developing palliative care at all levels: in clinical work, education and research.

“We are not used to talking about death and palliative care is a relatively new concept. We previously more or less ignored the needs of the dying but, in recent years, there has been a sharp increase in interest in end-of-life care”.

Many people want to die at home

There are currently just over 140 units in Sweden for palliative care. This can take the form of a hospice, care in the home or a few beds within ordinary healthcare facilities. But there are major differences between different regions in Sweden’s municipalities.

Birgit Rasmussen thinks that just as we now have maternal healthcare centres and specialist training programmes for midwives, we need centres and training specialising in palliative care.

“Just as there is a need for expert staff to help someone come into the world, so there is a need for expert staff to help someone leave it in the best possible way”.

Both international and Swedish studies show that many people want to die in their own homes, and in recent years there has been a substantial shift from dying in hospital to dying at home.

Always having access to medication

Research also shows that people who have been made aware that they are dying do so in the location of their choice to a higher degree. This also allows physicians to review their medication, for example. Medication is always to be available in an injectable form against pain, nausea, anxiety, etc.

If death has not been discussed, no prescriptions are ready when needed. Then it can take a long time to get relief from symptoms. It is also a question of greater peace and quiet in the last phase of life, and having discussed what “emergency services” might be relevant.

“A lot of this is about the next of kin and their right to support and security. If someting unexpected happens, they need to know whom to call and how to make contact within a few minutes. It is important that relatives get help and support in relation to various situations which can arise, as they may find themselves doing a lot of practical work when the end is near”.

Talking about death

Birgit Rasmussen has always combined her research with hospice work and she has never known a workplace with more laughter:

“You can talk about death for brief moments, but you can’t take just any amount of death talk. Many conversations in a hospice are about life, the everyday, how the football went yesterday and what you are going to have for dinner. A culture of slowness prevails and the philosophy is that the staff should always be available”.

Because even the dying talk about the future. You can’t constantly think about time having run out. It becomes like two parallel tracks, with patients sometimes talking about next summer, only to plan their own funeral in the next moment.

We have a great fear of discussing death but Birgit Rasmussen thinks that, from a public health perspective, we should talk more about the subject already in school, just as we talk about sexual health for example. It is also much better to talk about death with your next of kin when they are healthy. When someone gets ill or dies, it is a relief to know their wishes. How and where they want to be buried and whether they want to donate their organs.

“I don’t think I have ever met anyone who is not afraid of death. At the same time death is a driving force and without it life wouldn’t be worth anything”.

What can I do?

When the patient has undergone many treatments and there are no further options from a curative medical point of view, there is still a lot left to do from a human and palliative perspective. It is therefore important to ensure that the healthcare and nursing staff working with dying patients have sufficient knowledge. Many of them still find it hard to meet the needs of the dying and the questions, anguish and despair of their next of kin.

“Sometimes you can simply ask – ‘it feels as though you are anxious, what can I do?’ Often what’s needed is nothing remarkable – you have to dare to ask. We must create a society in which we live as well as we can – until we die. And where we don’t fail those in life’s final stages.

Text: Åsa Hansdotter

Illustration: Catrin Jakobsson