Collective memory – a sand sculpture that can be remoulded

“Thy throne rests on mem’ries from great days of yore, when worldwide renown was valour’s guerdon…”

is the translation of the words of the Swedish national anthem, which tries to construct a memory of a glorious national past. This type of attempt is not unusual, nor is its opposite – the suppression or alteration of shameful events.

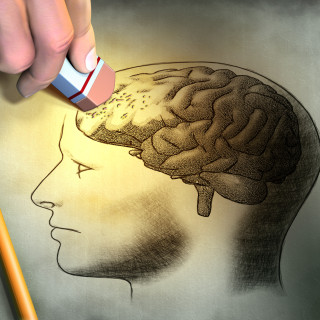

We like to think that history is set in stone. However, it is more like a sand sculpture that can be changed retrospectively”, says Professor of Central and Eastern European Studies Barbara Törnquist-Plewa.

She is interested in memories at group level, and she is not alone. Memory studies, in the sense of studies of how the past is used in the present, have in recent years developed into a new interdisciplinary research field. Today it includes research networks, conferences, and a dedicated journal – Memory Studies – in which articles are published from sociology, history, literature and film studies, and philosophy, among others.

Some of these studies are about national memories that are passed on through textbooks and official speeches. Others focus on more informal memories that are recounted within a community, profession or family. The conscious or unconscious goal is often to define oneself in relation to one’s surroundings: “this is what we are like, and this is what the others are like”.

There are a number of reasons why memory studies are on the rise. One reason is the identity research that developed in the 1980s as globalisation and increased travel demonstrated how mouldable people’s identities can be. Previously, a person’s identity was often regarded as a given from birth, whereas today we are expected to construct our own individual identity from a variety of optional elements.

“The question ‘who am I?’ links naturally to the question ‘who was I?’, i.e. what collective and personal memories form part of my identity.”

She views the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of the Cold War as another important reason for the blossoming of memory studies. Historical archives were opened, the EU expanded and the former Eastern bloc states started to deal with their memories from the Communist period. There are many painful memories that can lead to political conflicts.

“A Latvian film director has made a critical film about the memories of the Soviet collaboration with Hitler, which prompted strong reactions in Russia. The memories of the Hitler era can also turn up in other ways, such as in recent Greek demonstrations, which featured placards with images of Angela Merkel in a Nazi uniform. The question is whether it is possible to deal with the past at all in a way that makes the memories serve to unite and not to divide”, says Barbara Törnquist-Plewa.

She has conducted research on other memories from the Second World War, or rather on obliterated memories, of the Jews in the small Polish town of Szydlowiec. Three quarters of the town’s population was Jewish before the war, but the Jews were killed in Treblinka and the town is now inhabited solely by Poles. The synagogue has gone, the gravestones from the Jewish cemetery have been used as building material, old Jewish street names have been changed and interviews with the local population show that the older generation don’t like to remember the town’s Jewish history.

“In Poland, they are finally trying to deal with anti-Semitism and the repressed memories of how the Poles behaved towards the country’s Jews during the war. However, there is a lot of work still to do”, says Barbara Törnquist-Plewa.

“Sweden doesn’t have any such memories of conflict, but even here there have been shameful events and repressed memories, for example the sterilisation of people with learning disabilities and the treatment of the Sami, Roma and travellers. It is only in recent years that these memories have been highlighted”, says Barbara Törnquist-Plewa.

Text: Ingela Björck

Published: 2014