Clues can awaken hidden memories

The scent of a madeleine dipped in lime blossom tea awakened a flood of childhood memories for the main character in Marcel Proust’s famous novel about ‘lost time’. The madeleine is an example of a clue for the memory. In Proust’s case, the clue worked subconsciously, in other cases we can use clues to consciously try to recall the memories for which we are searching.

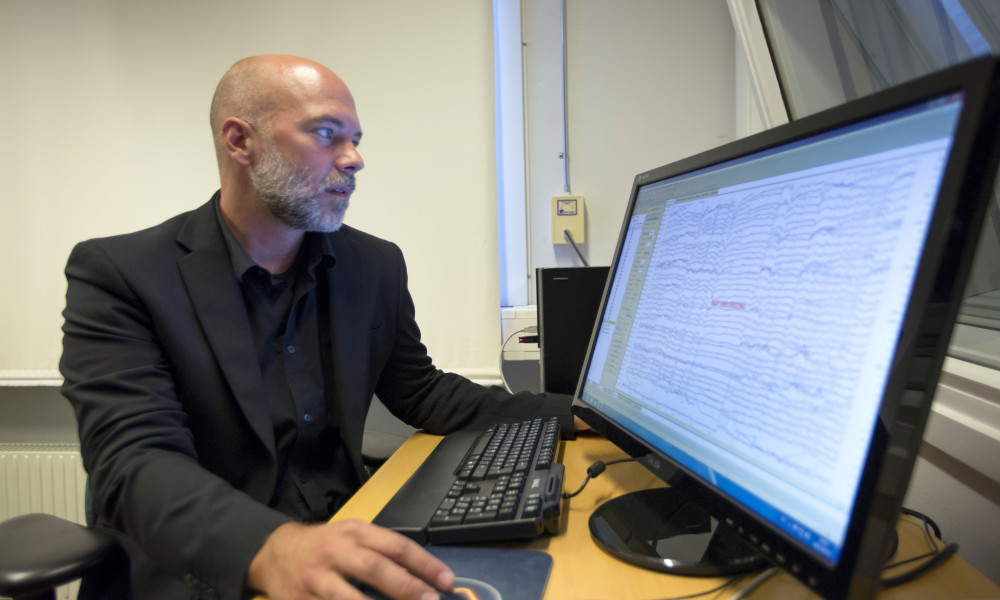

Mikael Johansson puts a gel on the electrodes on research subject Eril Larsen’s head to improve the electrical connection. The experiment is about brain activity in conjunction with repressed memories.

Professor of Psychology Mikael Johansson in Lund is one of Sweden’s leading memory researchers. He and his group study the mechanisms of memory and forgetting through both behavioural science experiments, in which subjects see pictures or words, and electrophysiological measurements and MRI studies of brain activity.

The memory researchers differentiate between different types. There is short- and long-term memory, conscious and subconscious memory, and episodic and semantic memory (events we have experienced versus neutral factual information).

The various memory systems are based in different parts of the brain and are partially independent of one another. They are all, however, essential to us.

A person who develops dementia or receives a memory-disrupting brain injury is transformed into a shadow of his former self. This applies despite the fact that memory is not particularly reliable.

“We interpret events and store them in our memory based on the understanding we have. If I saw an American football match I would remember players in strange outfits lying in a heap on the grass, whereas someone who knows more about the sport would remember the match completely differently”, says Mikael Johansson.

Thus far, nothing strange. It is less obvious that understanding and context also affect and may change the memories that are recalled. In one of the Lund researchers’ experiments, the research subjects received a list of words to memorise, including words like “wax”, “lamp”, “sun” and “day”. When they were given a new list of words to compare with the first list, almost all the subjects claimed that the word “light” was on the first list. This is a false memory, founded on the large number of words linked to the concept of light.

False memories are an area on which Mikael Johansson and his group have done a lot of work. They can be created through language as in the example above, or by engaging our senses.

“For instance, you can ask the subjects to imagine that they are breaking a matchstick. The more times they have to think about the situation – the match’s appearance, the feel of it in the hand, the sound when it breaks – the more likely it is that they will later remember that they really did carry out the action”, says Mikael Johansson.

This mechanism can create problems in certain contexts, such as cross-examination of witnesses in criminal trials. Questions have to be asked, but overly detailed questions do not help to bring out the truth; rather they help to create false memories.

When it comes to recalling a genuine memory, clues can help, by trying to find an association that awakens the memory. Mikael Johansson talks about recall “in agreement with the coding”, i.e. identifying something from the original situation that can serve as a prompt.

“An example that everyone will recognise is when you go into the kitchen and then can’t remember what you were intending to do there. It usually helps to go back to the place where you were when you first thought about the kitchen”, he says.

Forgetfulness is often regarded as something negative that is attributed to time wearing down our memories. However, this is not correct, according to Mikael Johansson. He and other memory researchers see forgetting as an active mechanism that benefits us by separating out unimportant and negative memories.

“We should of course learn from our memories, but it wouldn’t be healthy to repeatedly have to remember unpleasant events and failures. Forgetting therefore helps to make it more difficult to recall such memories. We all have that mechanism, although people with social phobias and depression experience it less.”

“An example that everyone will recognise is when you go into the kitchen and then can’t remember what you were intending to do there.”

Forgetting can also occur as “active repression of competing memory paths”, as memory psychologists would say. The term refers to the situations where the brain works so intensively on certain information that other, similar information is suppressed. One example is last-minute revision before an exam, which helps the student remember what he or she reads then, but which inhibits the memory of previous information. Another example is when someone who goes abroad and speaks another language can suddenly have difficulty finding the right word in his or her native language.

“However, the old knowledge, in this case the language, does not disappear. It is simply suppressed for as long as it causes a disturbance”, explains Mikael Johansson, providing an example of his own:

“I used to play bass, and have long lists of 1980s bassists in my head. They can stay in my memory for as long as they don’t cause a disturbance. However, if I were to start playing electric guitar and wanted to learn the names of electric guitarists, the bassists might get suppressed.”

Text: Ingela Björck

Photo: Gunnar Menander

Published: 2013