Lakes of the future

In many of Sweden’s lakes, decades of eutrophication have led to algal blooms. In the future, the lakes will also be warmer and browner. How does this affect life in our lakes? Most aquatic organisms are hardier than we think, and according to researchers, it is the eutrophication that we must – and can – do something about.

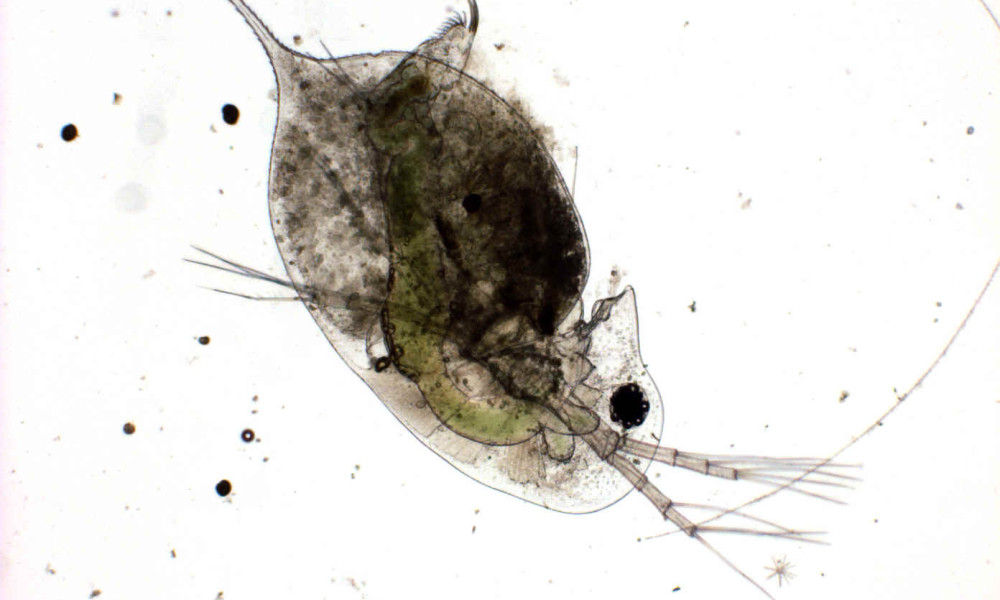

Most Swedish lakes are swarming with life. Just below the surface float plankton algae that use the light of the sun for photosynthesis. These become food for small crustaceans (zooplankton), which can be likened to the cattle of the lake, grazing on the algae. In many lakes there are fish that feed on zooplankton (for example, whitefish such as roach and bleak) and fish that feed on other animals (predatory fish such as pike-perch, perch and pike).

Lake food chain

Highly simplified, it can be regarded as a food chain, with plankton algae at the bottom and predatory fish at the top. Some lakes may not contain fish, and then zooplankton, such as water fleas, form the top of the food chain; the water in the lake is consequently clear. In other lakes, where there are no predatory fish and plankton-eating fish dominate, only a few of the small crustaceans survive and the plankton algae thrive. It has been shown that lakes react differently to environmental changes depending on the structure of the food chain.

Eutrophication

“As long as the eutrophication situation doesn’t change, we can expect more intensive and longer blooms of cyanobacteria.”

If a lake has all the organism groups in balance, then it is, from a human perspective, a well-functioning lake with clear water and a large number of predatory fish. By ‘fertilising’ the algae with an excess of nutrients from artificial fertiliser and other sources, we have in many cases altered the balance of the lake from being dominated by predatory fish to being dominated by plankton-eating fish and algae. Large algal blooms of poisonous cyanobacteria may result. There is a clear link between over-fertilisation, known as eutrophication, and which organisms that are dominant in a lake. But how will life in lakes be affected when the water becomes warmer and browner in the future?

Temperature rise

Researchers have shown that ongoing climate change is leading to rising temperatures in our lakes and seas. In the long run, on a scale of hundreds of years, we could see an increase of up to five degrees.

Most organisms are adapted to living within a certain temperature range. A rise in temperature could mean certain organisms grow faster and reproduce more successfully, whereas other species could do worse. It has been feared that certain species will not be able to adapt to a rise in temperature and that this could lead to catastrophic changes in our lakes.

Brownification

In parallel with the rise in temperatures, we also see increased ‘brownification’, where the water becomes browner in colour. Lakes and watercourses have become increasingly brown over the past 25 years as more humus (remains of decomposed plants) enters the water from the surrounding soil. Nowadays, most researchers believe that the phenomenon is a result of recovery from previous decades of acidification. In acidified land environments, humus binds strongly to soil particles. When acidification falls, the humus is released again and is washed into streams and lakes in soil water. One tangible effect of increased levels of humus is that it becomes more difficult to obtain drinking water; another is that the plants on the lake bed receive less light. The impact on life in the free body of water is less well understood.

Future water

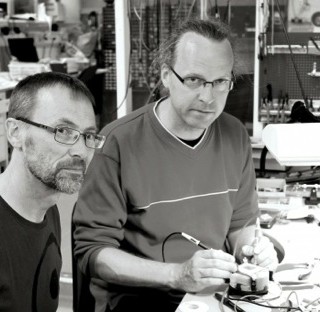

In order to study how rising temperatures and levels of brownification could affect water organisms, Lars-Anders Hansson and his research group at the Division of Aquatic Ecology, Lund University have used model lakes in 400-litre barrels. In some barrels, the environment was manipulated on the basis of a future scenario in which the temperature would rise by up to 3°C and brownness double over the next 25–75 years. The conclusions from the experiment are that the combination of a rise in temperature and brownification does not appear to present a problem for the plankton algae, crustaceans and fish that were studied in the experiment.

“A temperature increase of 3°C would mean some species grow a bit better and some a bit worse, but it’s not a disaster; we’re not going to lose a lot of species”, says Lars-Anders Hansson.

The increase in growth that will be caused by the temperature increase will be passed on up the food chain and benefit the organism group at the top, according to Lars-Anders Hansson. This could lead to even more predatory fish such as pike-perch in lakes where they are dominant.

Eutrophication the overriding problem

However, in a lake that is already eutrophicated, with a dominance of plankton-eating fish, the situation will become worse. More fish will mean an increase in algal blooms.

“As long as the eutrophication situation doesn’t change, we can expect more intensive and longer blooms of cyanobacteria, because they thrive when it becomes warmer”, Lars-Anders Hansson explains.

The positive aspect of these findings is that eutrophication is something we can actually prevent.

“If we can deal with eutrophication, moderate warming and brownification will not have any dramatic consequences for the life in our lakes”, says Lars-Anders Hansson.

New experiments have now started, to study a scenario that could occur several hundred years in the future. The question is what happens in a normal lake if the temperature rises gradually by 5°C and the amount of humus increases to four times current levels.

Text: Pia Romare

Photo: Kennet Ruona

Published: 2014